Mitral Regurgitation (MR) accounts for the vast majority of all mitral valve diseases.1 It has a prevalence of approximately 2% in the general population and is more common in the elderly population.3 Approximately 10% of people over the age of 70 have clinically meaningful MR.5

If left untreated, MR can lead to Heart Failure (HF), or deterioration of pre-existing HF, resulting in an increased number of hospital admissions and a substantial cost burden to health systems.6,8

Summary of the current guidelines

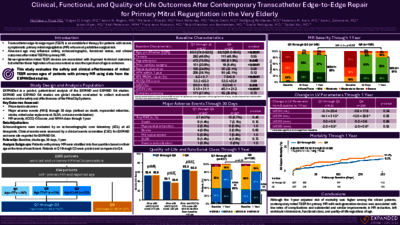

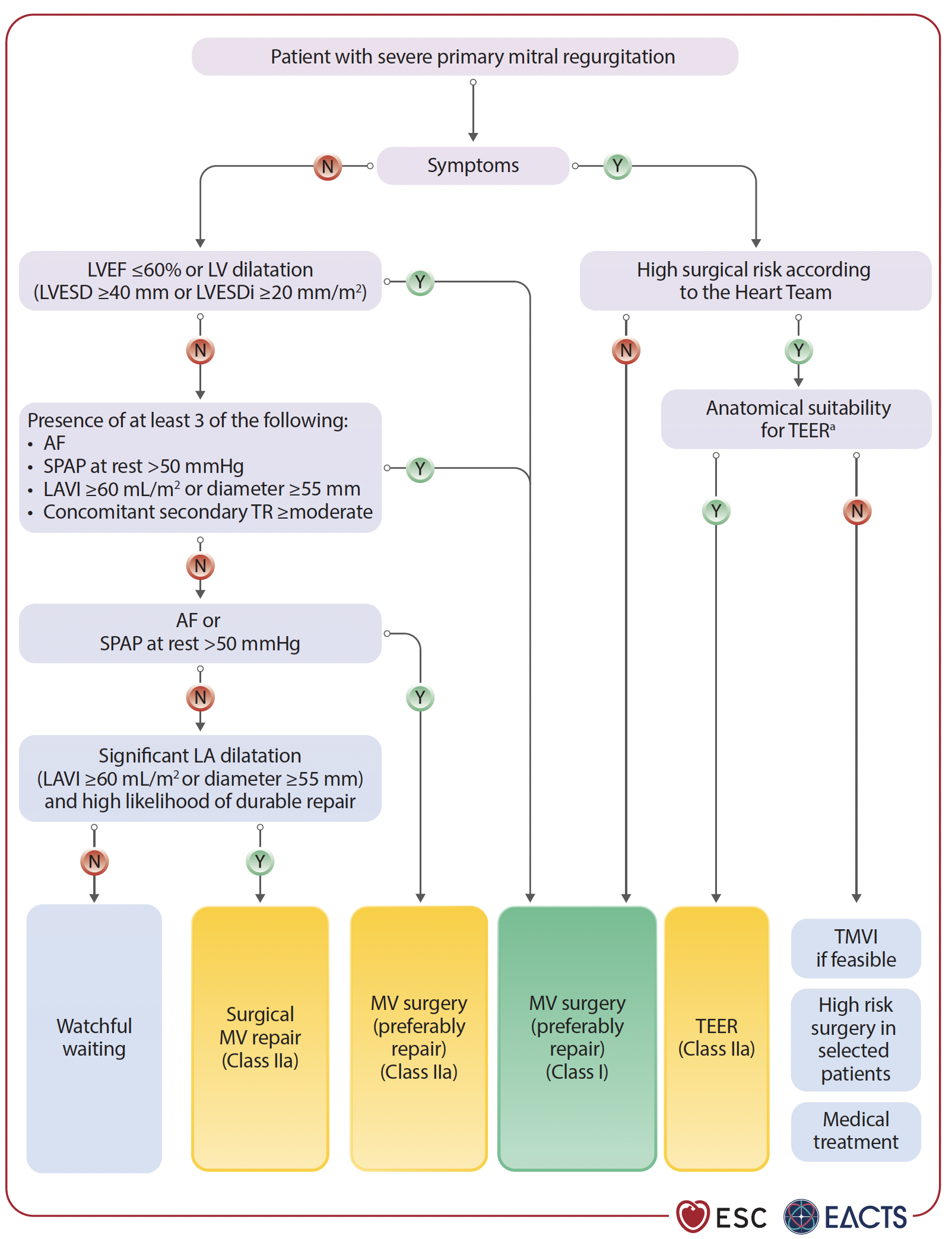

TEER is a recommended alternative for patients with primary mitral regurgitation who are inoperable or at high surgical risk—supported by Class IIa, Level of Evidence (LoE) B. Early intervention is key, even in asymptomatic cases, especially when signs of cardiac damage like tricuspid regurgitation or left atrial enlargement are present.

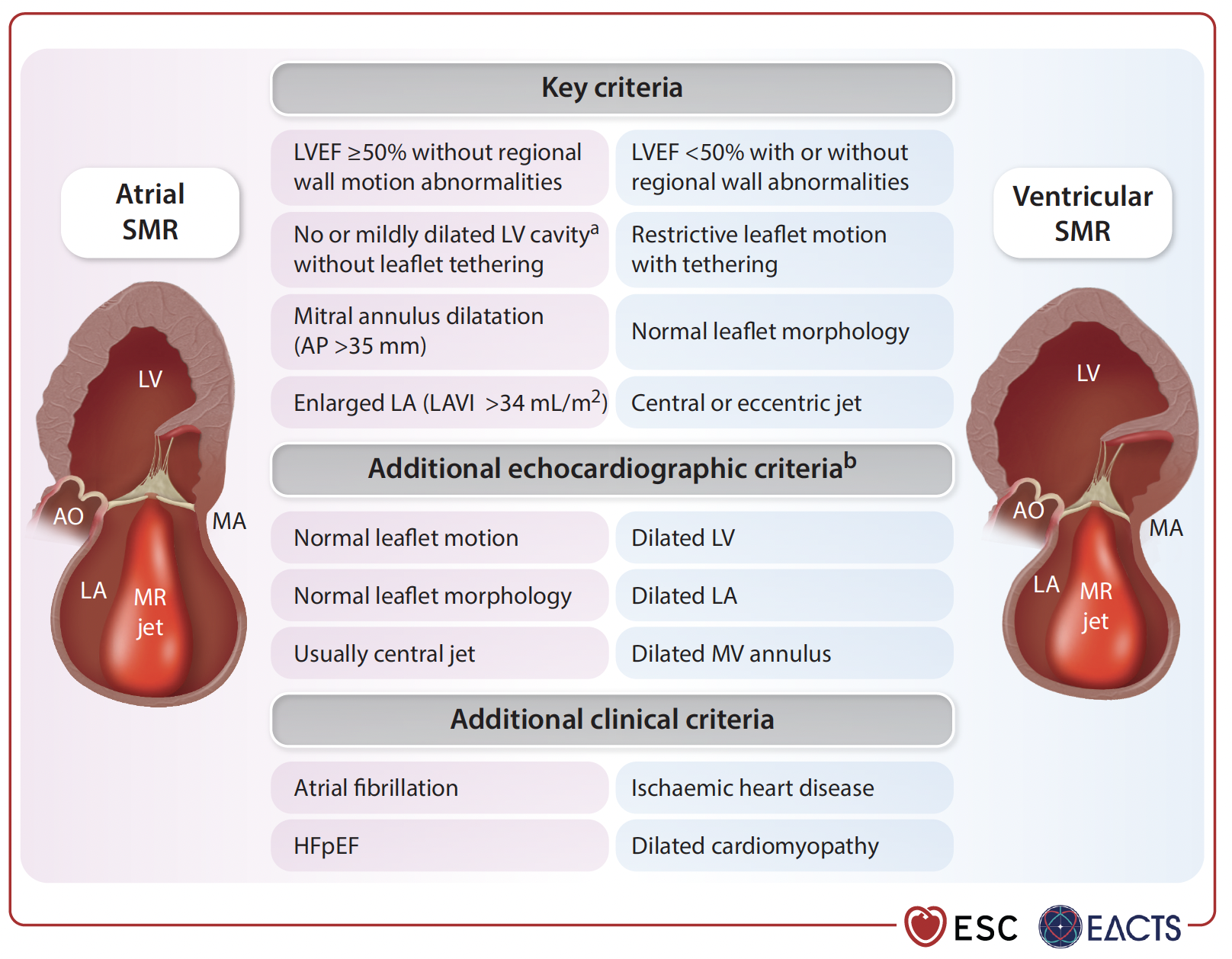

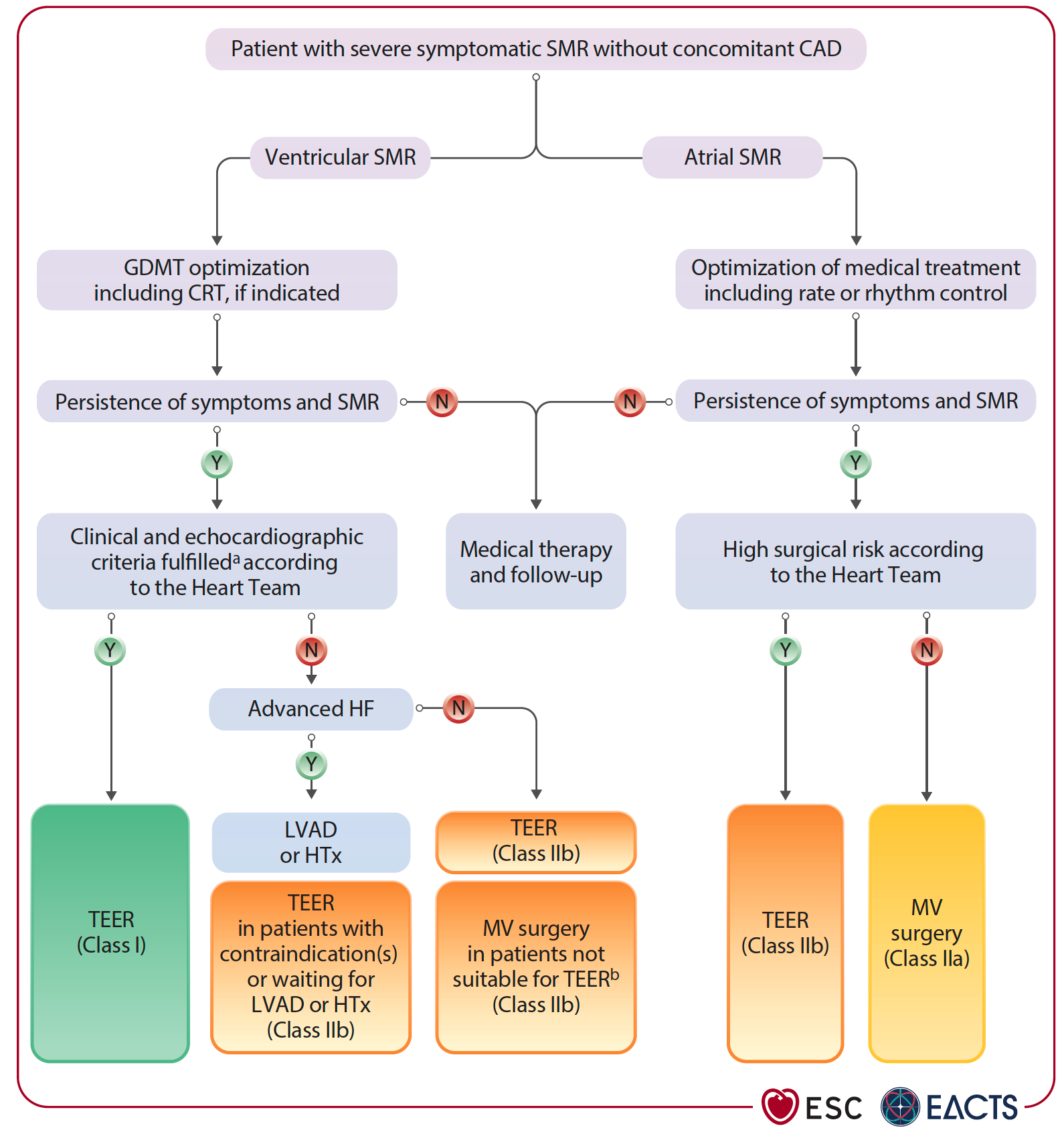

For secondary MR (SMR), guidelines now distinguish between ventricular and atrial types.

TEER is a Class I, LoE A recommendation for patients with ventricular SMR who remain symptomatic despite optimal medical treatment. In atrial SMR, surgery combined with AF ablation and LAAO may help, especially in patients with persistent symptoms and high stroke risk. TEER is also an option for those unsuitable for surgery, supported by a Class IIb, LoE B recommendation.

LEARN MORE:

The approach to mitral stenosis (MS) is evolving. Rheumatic MS is still treated with percutaneous mitral commissurotomy when anatomy allows, while surgery is reserved for complex cases. For degenerative MS linked to mitral annular calcification, guidelines now support transcatheter mitral valve implantation (TMVI) in select patients—reflecting growing expertise in this challenging area. TMVI has been deemed as Class IIb, LoE C.

LEARN MORE:

| PMR | SMR |

|---|---|

| Esc/eacts – Guidelines for the management of Valvular Heart Disease (2021)16 | |

Evaluation

| Evaluation

|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2020)22 | |

Initial diagnosis

Changing signs or symptoms

Routine follow-up

Exercise testing

| Diagnosis

|

| PMR | SMR |

|---|---|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF HEART FAILURE (2022)28 | |

N/A |

|

| ESC/EACTS – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2021)16 | |

In acute MR:

|

|

| HFA/EACVI/EHRA/EAPCI/ESC JOINT POSITION STATEMENT ON THE MANAGEMENT OF SMR (2021) | |

N/A |

|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2020)22 | |

|

|

| PMR | SMR |

|---|---|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF HEART FAILURE (2022)28 | |

N/A |

|

| ESC/EACTS – GUIDELINES ON THE MANAGEMENT OF VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2021)16 | |

|

|

| ESC – GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC HF (2021)15 | |

N/A |

|

| HFA/EACVI/EHRA/EAPCI/ESC JOINT POSITION STATEMENT ON THE MANAGEMENT OF SMR IN PATIENTS WITH HF (2021)29 | |

N/A |

|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2020)22 | |

|

|

| PMR | SMR |

|---|---|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF HEART FAILURE (2022)28 | |

N/A |

|

| ESC/EACTS – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2021)16 | |

|

|

| ESC – GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC HF (2021)15 | |

N/A |

|

| HFA/EACVI/EHRA/EAPCI/ESC JOINT POSITION STATEMENT ON THE MANAGEMENT OF SMR IN PATIENTS WITH HF (2021)29 | |

N/A |

|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2020)22 | |

|

|

| PMR | SMR |

|---|---|

| ESC/EACTS – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2021)16 | |

N/A |

|

| ESC GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC HF (2021)15 | |

N/A |

|

| ACC/AHA – GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH VALVULAR HEART DISEASE (2020)22 | |

|

|

Clinical Case clubs | Educational tools | Hot topics

Expert opinions | Live & online discussions

TV

HUB

- Lung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J.

2003;24(13):1231–43. doi.org/10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00201-X. - De Bonis M, Al-Attar N, Antunes M, et al. Surgical and interventional management of mitral valve regurgitation: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology

Working Groups on Cardiovascular Surgery and Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(2):133–9. doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv322. - Cahill TJ, Prothero A, Wilson J, et al. Community prevalence, mechanisms and outcome of mitral or tricuspid regurgitation. Heart. 2021;107(12):1003–9.

dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318482. - Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet.

2012;380(9836):37–43. doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. - Singh JP, Evans JC, Levy D, et al. Prevalence and clinical determinants of mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol.

1999;83(6):897–902. doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(98)01064-9. - Alegria-Barrero E, Chan PH, Paulo M, et al. Edge-to-edge percutaneous repair of severe mitral regurgitation–state-of-the-art for Mitraclip™ implantation. Circ J.

2012;76(4):801–8. doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1462. - Healthcare Commission. Pushing the boundaries. Improving services for people with heart failure. 2007. Available at: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20081006104707/

www.cqc.org.uk/_db/_documents/Pushing_the_boundaries_Improving_services_for_patients_with_heart_failure_200707020413.pdf (last accessed: 23 March 2023). - Braunschweig F, Cowie MR, Auricchio A. What are the costs of heart failure? Europace. 2011;13 Suppl 2:ii13–7. doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur081.

- Pedrazzini GB, Faletra F, Vassalli G, et al. Mitral regurgitation. Swiss medical weekly. 2010;140(3–4):36–43. doi.org/10.4414/smw.2010.12893.

- Mayo Clinic. Mitral valve regurgitation. 2019. Available at: www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mitral-valve-regurgitation/symptoms-causes/syc-20350178

(last accessed: March 2023). - Sparano DM, Ward RP. Management of asymptomatic, severe mitral regurgitation. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2012;14(6):575-83.

- Cioffi G, Tarantini L, De Feo S, et al. Functional mitral regurgitation predicts 1-year mortality in elderly patients with systolic chronic heart failure. Euro J Heart Fail.

2005;7(7):1112–7. doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.01.016. - Enriquez-Sarano M, Avierinos J-F, Messika-Zeitoun D, et al. Quantitative determinants of the outcome of asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med.

2005;352(9):875–83. doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa041451. - Grigioni F, Tribouilloy C, Avierinos J-F, et al. Outcomes in mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets a multicenter European study. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging.

2008;1(2):133–41. doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.12.005. - McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the

diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA)

of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599–3726. doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. - Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of

valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Euro Heart J. 2022;43(7):561–632.

doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395. - Gaasch WH, Meyer TE. Left ventricular response to mitral regurgitation: implications for management. Circulation. 2008;118(22):2298–2303.

doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.755942. - National Health Service. Mitral valve problems. 2020. Available at: www.nhs.uk/conditions/mitral-valve-problems(last accessed: March 2023).

- American Heart Association. Problem: Mitral Valve Regurgitation. 2016. Available at: www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-valve-problems-and-disease/heart-valveproblems-and-causes/problem-mitral-valve-regurgitation (last accessed: March 2023).

- Spieker M, Kelm M, Westenfeld R. Moderne Diagnostik der Mitral- und Trikuspidalklappe – was ist wirklich notwendig? Aktuelle Kardiologie. 2017;6:265–70.

doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-115534. - Young A, Feldman T. Percutaneous mitral valve repair. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(1):443. doi.org/10.1007/s11886-013-0443-6.

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, 3 authors, et al.. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary:

A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e35–e71.

doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000932. - Ling LH, Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, et al. Clinical outcome of mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(19):1417-1423.

doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199611073351902. - Mirabel M, Iung B, Baron G, et al. What are the characteristics of patients with severe, symptomatic, mitral regurgitation who are denied surgery? Eur Heart J.

2007;28(11):1358–65. doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm001. - Nielsen SL. Current status of transcatheter mitral valve repair therapies - From surgical concepts towards future directions. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2016;50(5-6):367-376. doi.org/10.1080/14017431.2016.1248482

- Asgar AW, Mack MJ, Stone GW. Secondary mitral regurgitation in heart failure: pathophysiology, prognosis, and therapeutic considerations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1231–1248. doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.009

- Iung B, Baron G, Tornos P, et al. Valvular heart disease in the community: a European experience. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2007;32(11):609-661. doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2007.07.002

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895–e1032. doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

- Coats AJS, Anker SD, Baumbach A, Alfieri O, von Bardeleben RS, Bauersachs J, et al. The management of secondary mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure: a joint position statement from the Heart Failure Association (HFA), European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), and European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) of the ESC. Euro Heart J. 2021;42(13):1254–1269. doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab086

- European Heart Journal, Volume 46, Issue 44, 21 November 2025, Pages 4635–4736, doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf194